|

|

|

|

|

Low sugar population, health testing, book reviews

|

|

|

LSP the evidence that they don’t get

CAWD:

Combine with 1-B-LSP intro

Mystery:

This book is

about solving why those

populations on a low sugar diet (LSPs) have a different set of illnesses. It is about what has been known since 1982 called conditions

associated with the western diet (CAWD),

and before that as conditions of civilization,

and prior as conditions of affluence. It arrives at the cause, fructose, and how

through fructosylation (fructation) it damages the mitochondria (MTD), and when

consumed significantly

above what cellular repair system can repair, the altered functions of the

cells throughout the body increase the risks for all the CAWD, and especially

among the elderly in what is known as age

related conditions. Since

the seminal work by Burkett and Trowel in 1981, the science solving that

mystery has made an incontrovertible case against fructose. The second

of 6 Sections is on sugars. The

third section is on the mitochondria, which fructose “modifies” through the Trojan

horses of proteins and polyunsaturated fats (PUFAs): it bonds to them in

a process of fructation (also labeled fructosylation) in the cytosol, and some

of those damaged molecules are transported into the mitochondria a topic in

Section 3, which is devoted to the mitochondria and its altered performance,

most significantly is the reduced production of ATP, the causal factor for

insulin resistance (IR) in the

liver. Section 4 names what I considered

the most significant changes the

damage goods cause operating through a diminished production of ATP and other

chemicals produced by the mitochondria.

On the big demon list is a reduced production of collagen, sensitivity

to uric acid, and a reduced rate of autophagy (RRA). RRA explains why low

sugar populations are resistant to, for example the effect of cigarettes (the

degree correlates to the percentage of those who life-long limit their sugar to

under 24 grams a day (WHO’s dietary recommendation for sugar intake for women).

Section

5 is on those conditions that are called age related health conditions but

are more accurately called conditions associated with the western diet (CAWD) since they are nearly unknown

among the low sugar populations (LSPs).

Thus by Section 4 is set out the cause

for our health disaster, and the association between mitochondrial dysfunction

(MTDD) and the conditions, the topic

for section 5. And since most readers

would be interested in what to do repair our fructose damage mitochondria and

the consequences there from, as a Benthamite (utilitarian) I am morally

obligated to write a Section 6 on

what to do. Simply limiting sugar to 24

grams a day will only very slow promote healing among adults, much quicker

among children, and at a moderate rate among young adults. There are ways to

double and quadruple that

rate, and this is what Section 6 is about.

Oh,

and as a Benthamite I am also obligated to set the record straight concerning

tobacco science and its consequence.

Thus many bromides [truths that on the shelf of time are stable] that

are engraved in textbooks and taught by key opinion leaders (KOLs) and their

dupes; these bromides

will be dumped into my acid bath of basic science. The foundation of this book,

and thus the

bath is to piece together into a sold fabric the pieces of science that answer

the basic questions of why we get what are now as conditions associated with

the western diet, and the LSPs don’t get them.

The test is the modus operandi, the why is this happening. Why do we

get cancer, and they don’t? Why is fructose very different than

glucose? Why does the LSPs mitochondria

outperform the mitochondria of the HSPs?

Why does this difference effect health, and how? The answers are

there is journal articles,

thousands of journal articles, many of them tangent, and a few seminal covering

a large area of research. I let the

journal speak. This

is more than solving a mystery, it is also about wellness. The amount of harmful

bromide spread as

healthful upon the minds of physicians, dieticians, and the public by KOLS and

their dupes, has created is exposed then in Section 6, there is what to do that

promotes healing.

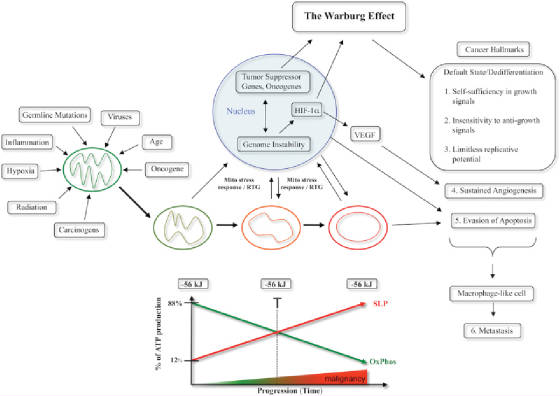

2. CAWD

I am not

the first to see the association of MTD dysfunction and CAWD: A wide range of seemingly unrelated

disorders, such as schizophrenia,

bipolar disease, dementia, Alzheimer's disease, epilepsy, migraine headaches,

strokes, neuropathic pain, Parkinson's disease, ataxia, transient ischemic

attack, cardiomyopathy, coronary artery disease, chronic fatigue

syndrome, fibromyalgia, retinitis pigmentosa, diabetes, hepatitis C,

and primary biliary

cirrhosis,

have underlying pathophysiological mechanisms

in common, namely reactive oxygen species (ROS)

production, the accumulation of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA)

damage, resulting in mitochondrial dysfunction—link 2007 .

Insulin

resistance is a result of two complimentary effects, ones is that the damage to

MTD causes both reduced size of MTD and reduced absorption of and metabolism of

glucose (and presumable fructose and galactose which are also metabolized in

MTD. A 2006

study found among other things: glycogen synthesis

was decreased by over

50% in patients with type 2 diabetes. That study also found consistent with

population studies that the children of diabetics have similar reduction in

metabolism of glucose: “Further analysis

has found that the reduction in mitochondrial function in the insulin-resistant

offspring can be mostly attributed to reductions in mitochondrial density.” This finding is supported by another which

measured the size of MTD of three groups of 10 each, lean, slightly obese and

t2d.

3. Biomarkers of LSPs:

What is normal biomarkers for those on the

western diet, isn’t for LSPs on a paleo diet

Table 2: Systolic

blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP)

at age 40–60 years in hunter–gatherers and horticulturalists (mm Hg) 26,

67–69

|

Population -----

|

Men

|

|

Women -

|

|

|

|

SBP---- -

|

DBP-- ----

|

SBP

|

DBP -----

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bushman

|

108

|

63

|

118

|

71

|

|

Yanomamo

|

104

|

65

|

102

|

68

|

|

Xingu

|

107

|

68

|

102

|

63

|

|

Kitava

|

113

|

71

|

121

|

71

|

Table 3: Systolic

blood pressure and diastolic

blood pressure in Yanomamo Indians 69.

|

Age years --------

|

Men -----------

|

Women------

|

|

0-9

|

93/59

|

96/62

|

|

10-19

|

108/67

|

105/65

|

|

20-29

|

108/69

|

100/63

|

|

30-39

|

106/69

|

100/63

|

|

40-49

|

107/67

|

98/62

|

|

50 +

|

100/64

|

106/64

|

Figure 1, Fasting

plasma insulin (IU/mL) in Kitava horticulturists (first

number) versus healthy Swedes (second number).74 Transposed

from graph by JK

|

Men 25-39

|

40-59

|

60-74

|

|

Women 25-39

|

40-59

|

60-74

|

|

3.9 vs 5.7

|

3.5 vs 6.85

|

3.55 vs 7.65

|

|

3.5 vs 6.2

|

3.85 vs 3.9

|

3.8 vs 7.25

|

Figure 3, Fasting

plasma leptin (ng/mL) in Kitava horticulturalists versus

healthy Swedes. 92

|

Men <40

|

40-59

|

60 +

|

|

Women < 40

|

40-59

|

60 +

|

|

1.7 vs 3.4

|

3.5 vs 5.2

|

3.7 vs 7.2

|

|

5.95 vs 11.4

|

3.2 vs 14.1

|

3.95 vs 19.1

|

Figure 4 Fasting plasma leptin

(ng/mL) in Ache Indians versus

American marathon runners.83

Ache (Axe people) are indigenous hunter-gatherers of eastern Paraguay.

|

Ache

|

American

runners

|

|

1.15

|

2.20

|

Systematic

recording of dietary intake while living in the forest entirely off wild foods

suggests that about 80% of their energy in the diet comes from meat, 10% from

palm starch and hearts, 10% from insect larva and honey, and 1% from fruits.

Total energy intake is approximately 2700 kcal per person daily.[1]

Figure 7, Maximum

oxygen consumption in various populations (mL/kg/min). 67

|

Lufas

|

Maasai

|

Eskimos

|

Lapps

|

Warao

|

IKung

|

Average American

|

|

67

|

58.5

|

57

|

53

|

51

|

49

|

42

|

Note, JK: the IKung are desert dwellers in South

Africa and the Warao live in costal Jungle regions of Northern South America

all of which the temperature limits physical excursion; while the Lapps and

Eskimos for most of the year can’t breathe deeply. The Maasai live

on the plains of Kenyan and Tanzania. The Lufas, I

couldn’t find a reference to, the link

#97 to the abstract didn’t

reference oxygen consumption, and the

full article is not available for free. Oxygen

consumption is associated with,

cardiovascular fitness. After insulin resistance, fitness is the

best marker for health/longevity——link to senior runners.

Cardiovascular fitness is of all measurement the best predictor health

and quality of life. So why is there so

a difference in all of this markers for health of LSPs and HSPs. Figure 1 and

4 contain the answer, IR. Children on the western diet develop IR. Many by comparison to the LSPs are born with

IR. A mother with IR pass on through

fetal environment IR. Her elevated glucose causes cellular responses that

affect the number of receptors for the transport of glucose into cells and

other cellular functions. It is a fetal

adaptation to the dietary environment the child will be exposed to. These changes

on a cellular level or further

established by the frequently consumption of excessive sugar. What I predict

is that at some point, even

with physical training and change of diet, obtaining the levels of insulin and

leptin in figures 1 & 4 will not be possible. My guess would be by the 25th

year—could well be in the teen years.

4. Defective mitochondria:

What is driving the damage to the

mitochondria. The literature finds 3

causes: oxidative stress from the

reactive chemical created in metabolism, in addition there is the role of uric

acid produced during the metabolism of fructose in the mitochondria, there is

fructosylation, and with damage to the mitochondria the repair systems of the

mitochondria are not functioning at optimal levels. Evidence from defective

mitochondria comes

from lower use of oxygen and smaller size in those with type 2 diabetes--at 2005, 2006. “A reduced basal ADP-stimulated and maximal mitochondrial

respiratory

capacity underlies the reduction in in vivo mitochondrial function, independent

of mitochondrial content [number of mitochondria]. A reduced capacity at both

the level of the

electron transport chain and phosphorylation system underlies this impaired

mitochondrial capacity [less ATP molecules]”--at 2008. As maintained those with IR in

the liver which is caused by the

high fructose diet will develop in the liver and later in other tissues

defective mitochondria similar the diabetic but to a lesser degree. This will

causes a decrease in the

production of ATP through the Krebs cycle, and as a consequence an increase in

cellular and serum glucose. In

the liver and conversion rate of

glucose to glycogen and the production of ATP has decrease due to defective

mitochondria and the effects of inflammation caused by a fatty liver, thus

slowing the utilization of glucose and raising serum glucose, the hallmark of IR—see

2008

and 2011.

Cells throughout the body already load with

glucose become resistant to the uptake of more glucose as the liver’s functions

decline. Through a feedback mechanism these body cells become resistant to the

uptake of more glucose. Added to this is the Crabtree effect: a high level of

glucose down regulates glucose

metabolism (inhibition of respiration), “that effect was strongly antagonized

by fructose 1,6-bisphosphate (F16bp). . . .

as able to inhibit mitochondrial respiration. . .” [2] This

combination of factors explains the development of insulin resistance in

tissues besides the liver.

Fructose

has a very low insulin index because over 95% is taken to the liver by the

hepatic portal vein where it is phosphorylated there thus making it incapable

of passing out of the liver like glucose--Wiki.

invisible to insulin by being taken from the

serum on first pass from the small intestines via the hepatic portal vein to

the liver. This explains why fructose

though invisible to insulin, has a glycemic index (which measures glucose

uptake from foods) of fructose is between 19 to 23, while glucose is rated at

100, and sucrose at 60 (thus not 50). The

rise in insulin is because of the slower uptake

of glucose through the GLUT-5 transport system into the hepatocytes.

“Perturbations in the regulation of glucose

and lipid metabolism are both involved in the insulin resistance in skeletal

muscle in obesity and type 2 diabetes (2,3). Previously, our

laboratory (30) as well as others (31) have observed that

the severity of skeletal muscle insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes and

obesity is related to diminished activity of oxidative enzymes. In addition,

accumulation of triglycerides in skeletal muscle is also correlated with the

severity of insulin resistance and with diminished oxidative enzyme activity in

these disorders(23) [not causal] . . .

The mitochondria area was reduced by ~35% in type 2 diabetes and obesity.” at

2002. Size and shape of mitochondria are strong

associated with compromised functioning of the mitochondria—see for example the

work of Nobel Laureate Otto Warburg.

Research is needed to find out if this change also occurs with IR.

Decline

in skeletal muscle mitochondrial function with aging humans[3]

[1] Wiki, 12/18 Ache https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ach%C3%A9. The

article’s discussion of their diet puzzles on why the men prefer to hunt rather

than gather food for which coconuts are plentiful and supplies 25% more energy

per hour of labor than hunting. I aver

that hunting reduces boredom more than gathering foods such as coconuts. Given this it explains why another article

finds that the average for hunter-gatherers is 60% of calories from animals and

insects.

[2] Kelley, David,

Jing He, et al Oct 2002, Dysfunction of

Mitochondria in Human Skeletal Muscle in Type 2 Diabetes

[3] Kevin

Short, Maureen Bigelow, et al, April 2005, Decline

in skeletal muscle mitochondrial function with aging humans

|

|

|

Review of Burkett & Trowell -- include

WESTERN DISEASES:

THEIR EMERGENCE AND PREVENTION. By H.C. Trowell

and D.P. Burkett

Burkitt.

Cambridge, MA, Harvard University

Press, 1981. 456 pp.

$40.00.

During travels through

developing and industrialized

countries in the West

Pacific, Far East, and Central America, I

often wondered about the

state of

health of these peoples and those in similar countries

around

the world. I was especially curious about

the prevalence of chronic

non-infectious diseases and how these were

related to culture, environment,

diet, and personal

health practices. Furthermore,

I was intrigued

about the extent to which Western

acculturation directly or indirectly

affected health.

These questions are now answered on

a global basis in this book edited

by two eminent physicians,

H.C. Trowell and D.P.

Burkitt. I applaud their efforts and those of the contributors in presenting current

information on this timely and

significant aspect of international health and epidemiology.

As is succinctly

stated in their preface, "this book attempts

to discuss

the commoner diseases of civilization." In essence, these diseases are

ones felt by the editors

to be

characteristic of modern Western

industrialized societies:

metabolic and cardiovascular diseases (e.g., coronary artery disease, hypertension, diabetes

mellitus, cerebrovascular

disorders); intestinal diseases (e.g., appendicitis, diverticular disease, cancer, hemorrhoids, polyps, constipation);

and a variety of

others, including

nephrolithiasis, gout,

pernicious anemia,

thyrotoxicosis, and breast and lung cancer.

The

major chapters in the book study

several specific populations from

all corners of the earth. They

are collected in sections

under the concepts of hunter-gatherers, peasant-agriculturists,

migrants and mixed ethnic

groups, and

the Far East. The people described include Inuit Eskimos, Australian

aborigines, Pacific Island groups,

South African

populations, Hawaiian ethnic groups,

and the population

of Taiwan and China. The chapters

are thorough and well-written, with

numerous and current references. The 34 contributors,

of whom the majority are physicians, have

had extensive experience living and working with

these populations. In

each chapter, discussions

cover population

demographics, cultural aspects of the

diet, and important studies on

disease-specific morbidity

and mortality

data. A common thread running through

all of the chapters is the role of

diet (carbohydrate, fat,

fiber, and protein components) and known health

risk factors (smoking, sedentary living, alcohol consumption,

stress concomitants,

and individual susceptibility)

as associated

factors in the epidemiology

of these diseases. Topics are presented

in an informative manner for the reader to

consider, without biased "breast-beating"

over conjectured dogmas. Another section of chapters

is concerned with the international epidemiology

and environmental aspects

of certain important

diseases, including multiple sclerosis,

cancer, and the

arthritides. The current state

of the art

in the treatment and prevention

of cardiovascular diseases,

intestinal disorders, and

diabetes mellitus is also examined. There are only two

shortcomings of this book,

but they are inherent in

its design and do not detract from its purpose.

In some instances, the available orbidity

and data are limited and

are not able to

be broken down into specific rates,

i.e., by age group. Second, the subject of psychiatric diseases is not covered;

however, this would entail a separate text.

Western Diseases: Their

Emergence and Prevention

stands on its own merits

as a welcomed and necessary reference for

those

involved in the fields of international health and epidemiology. I

also highly recommend this

book to anyone who anticipates working in

the fields of overseas health care or

exploration medicine.

MARK L. DEMBERT

Department of

Epidemiology and

Public Health

Yale University School of Medicine

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

https://www.lrb.co.uk/v03/n24/thomas-mckeown/the-burden-of-prudence-industrialisation-and-disease

The Burden of

Prudence – Industrialisation and Disease

Thomas McKeown

Hugh Trowell and Denis

Burkitt are a distinguished physician and surgeon who have spent most of their

professional lives in Africa; with T.L. Cleave and G.D. Campbell, they have

probably contributed more than anyone else to our understanding of the relation

between the health problems of developed and developing countries. In Western

Diseases they bring together reports by 34 contributors, who

describe their experience of changes in the pattern of disease in several

countries as Westernisation occurs. There are four main lines of evidence,

which the editors admit are not all equally secure. 1. Until recently many of

the non-communicable diseases now predominant in the West were uncommon or

absent in hunter-gatherers and peasant agriculturists. 2. When these

populations change from their traditional ways of life to those of the

developed countries, they begin to exhibit the Western pattern of disease. 3.

The incidence of some of the diseases has declined in Western populations which

have reversed certain features of their lifestyle to bring it closer to that of

peasant agriculturists. 4. Of the multiple influences responsible for the

Western pattern of disease, dietary changes are probably the most important.

The full text of this book

review is only available to subscribers of the London Review of Books.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|