|

Psychiatric Drugs |

|

Psychiatric drugs 32% bias reporting in journal articles

Positive bias from 11 to 69%: a study compares

raw data to journal published data. The study compares the data raw data supplied

the FDA to the selected data published in journal articles. As expected, because the studies were done as part of an overall

strategy to market drugs, the results were manipulated for that end. In all 37

studies the positive bias was 11 to 69%. In other words every journal article

based on clinical trials of psychiatric medications overstates substantially their positive results. And negative results are no published. There of course is no reason to believe that what motivates

Pharma for psychiatric drugs is not also operating for all their published studies.

Volume 358:252-260, http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/short/358/3/252 Selective Publication of Antidepressant Trials and Its Influence on Apparent Efficacy Erick H. Turner, M.D., Annette M. Matthews, M.D., Eftihia Linardatos, B.S., Robert A.

Tell, L.C.S.W., and Robert Rosenthal, Ph.D.

ABSTRACT

Background Evidence-based medicine is valuable

to the extent that the evidence base is complete and unbiased. Selective publication of clinical trials

— and the outcomes within those trials — can lead to unrealistic estimates of drug effectiveness

and alter the apparent risk–benefit ratio. Methods We obtained reviews from the Food

and Drug Administration (FDA) for studies of 12 antidepressant agents involving

12,564 patients. We conducted a systematic literature search to identify matching publications.

For trials that were reported in the literature, we compared the published

outcomes with the FDA outcomes. We also compared the effect size derived from the published reports

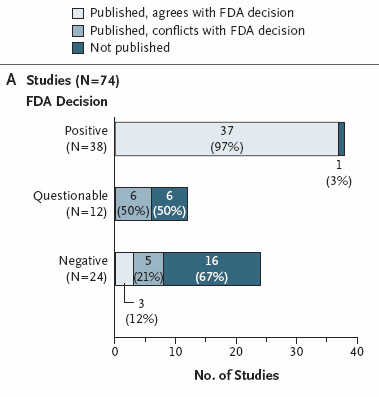

with the effect size derived from the entire FDA data set. Results Among 74 FDA-registered studies,

31%, accounting for 3449 study participants, were not published. Whether

and how the studies were published were associated with the study outcome. A total of 37 studies

viewed by the FDA as having positive results were published; 1 study viewed as positive was not published.

Studies viewed by the FDA as having negative or questionable results were, with 3 exceptions, either not

published (22 studies) or published in a way that, in our opinion, conveyed a positive outcome (11 studies).

According to the published literature, it appeared that 94% of the trials conducted were positive. By

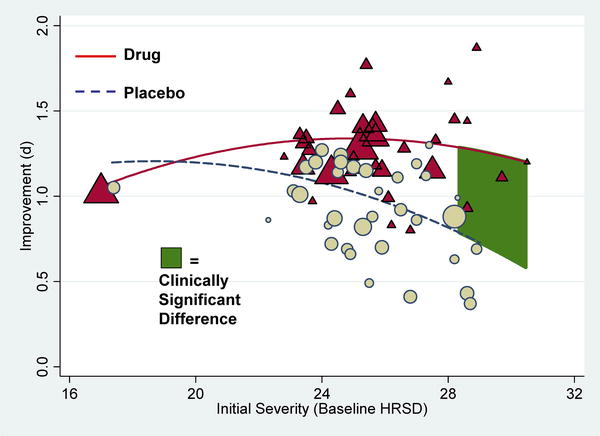

contrast, the FDA analysis showed that 51% were positive. Separate meta-analyses of the FDA and journal data sets

showed that the increase in effect size ranged from 11 to 69% for individual

drugs and was 32% overall. Conclusions We cannot determine whether the

bias observed resulted from a failure to submit manuscripts on the part of authors and sponsors, from

decisions by journal editors and reviewers not to publish, or both. Selective reporting of clinical trial

results may have adverse consequences for researchers, study participants, health care professionals, and

patients. Full text at http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/full/358/3/252 |

||

|

Pieces from the full text Data from FDA Reviews We identified the phase 2 and 3 clinical-trial programs for 12 antidepressant agents approved by the FDA

between 1987 and 2004 (median, August 1996), involving 12,564 adult patients. For the eight older antidepressants,

we obtained hard copies of statistical and medical reviews from colleagues who had procured them through

the Freedom of Information Act. Reviews for the four newer antidepressants

were available on the FDA Web site. This study was approved by the Research and Development Committee of

the Previous studies have examined the risk–benefit ratio for drugs after combining data from regulatory

authorities with data published in journals.3,30,31,32 We built on this approach by comparing study-level data from the FDA with matched data from journal

articles. This comparative approach allowed us to quantify the effect of selective publication on apparent

drug efficacy. From CL Psy A commentary on the results of the study

was published on A whopper

of a study has just appeared in the New England Journal of Medicine. It tracked each study antidepressant submitted to the FDA, comparing the results as seen by the FDA in comparison with the

data published in the medical literature. The FDA uses raw data from the submitting drug companies for each study. This makes

great sense, as the FDA statisticians can then compare their analyses to the analyses from drug companies, in order to make

sure that the drug companies were analyzing their data accurately. After studies

are submitted to the FDA, drug companies then have the option of submitting data from their trials for publication in medical

journals. Unlike the FDA, journals are not checking raw data. Thus, it is possible that drug companies could selectively

report their data. An example of selective data reporting would be to assess depression using four measures. Suppose that

two of the four measures yield statistically significant results in favor of the drug. In such a case, it is possible that

the two measures that did not show an advantage for the drug would simply not be reported when the paper was submitted for

publication. This is called "burying data," "data suppression," "selective reporting," or other less euphemistic terms. In

this example, the reader of the final report in the journal would assume that the drug was highly effective because it was

superior to placebo on two of two depression measures, left completely unaware that on two other measures the drug had no

advantage over a sugar pill. Sadly, we know from prior research that data are often suppressed in such a manner. In less severe cases, one might just switch the emphasis placed on various outcome measures. If a measure

shows a positive result, allocate a lot of text to discussing that result and barely mention the negative results. From an amoral, purely financial

view, there is no reason to publish negative trial results. The NJE article stated “For each drug, the effect-size value based on published

literature was higher than the effect-size value based on FDA data, with increases ranging from 11 to 69%.” The drugs that were found to have increased their effects as a result of selective publication and/or data manipulation: ·

Bupropion (Wellbutrin) ·

Citalopram (Celexa) ·

Duloxetine (Cymbalta) ·

Escitalopram (Lexapro) ·

Fluoxetine (Prozac) ·

Mirtazapine (Remeron) ·

Nefazodone (Serzone) ·

Paroxetine (Paxil) ·

Sertraline (Zoloft) ·

Venlafaxine (Effexor) That is every single drug approved by the FDA for depression between 1987 and 2004. Just a few of many tales of data

suppression and/or spinning can be found below: ·

Data reported on only 1 of 15 participants

in an Abilify study ·

Data hidden for about 10 years on

a negative Zoloft for PTSD study ·

Suicide attempts vanishing from a Prozac study ·

Long delay in reporting negative results from an Effexor for youth depression study ·

Data from Abilify study spun in dizzying

fashion. Proverbial lipstick on a pig. ·

A trove of questionable practices

involving a key opinion leader ·

Corcept heavily spins its negative antidepressant trial results Another article based on the NEJM study

at February 26, 2008 — 7:59am ET Here's a study guaranteed to put almost every drugmaker on the defensive. Researchers analyzed every

antidepressant study they could get their hands on--including a bunch of unpublished data obtained via the U.S. Freedom of

Information Act--and concluded that, for most patients, The new paper, published

today in the journal PLoS Medicine, breaks new ground, according to The Guardian, because the researchers got access for the first time to an apparently

full set of trial data for four antidepressants: Prozac (fluoxetine), Paxil (paroxetine), Effexor (venlafaxine), and Serzone

(nefazodone). And the data said..."the overall effect of new-generation antidepressant medication is below recommended criteria

for clinical significance." Ouch. The study could have a ripple effect, affecting prescribing guidelines and even prompting questions

about how drugs are approved. "This study raises serious issues that need to be addressed surrounding drug licensing and how

drug trial data is reported," one of the researchers said. In other words, all trial data needs to be made public.

INTERNAL SITE SEARCH ENGINE by Google

|