|

Antidepressants Proven useless for most

|

|

Over and over again we find that new isn’t better. One more example: The new generation of anti-depression medications (SSRs) fail to be more effective than a placebo--but for one small group. This study confirms a previous study. 10

years ago I read articles that Prozac doesn't work, but the FDA and the industry work together. From Fiercepharma February 26, 2008

|

|

Here's a study guaranteed to put almost every drug maker on the defensive. Researchers analyzed every antidepressant

study they could get their hands on--including a bunch of unpublished data obtained via the U.S. Freedom of Information Act--and

concluded that, for most patients, SSRI antidepressants are no better than sugar pills. Only the most severely depressed get

much real benefit from the drugs, the study found. That's quite a conclusion, considering that antidepressants are among the world's top-selling

meds, accounting for billions in revenues every year. Manufacturers rushed to defend

their products, saying that regulators in many countries had reviewed the data and concluded the drugs were effective. GlaxoSmithKline,

for instance, said that this new study only looked at "a small subset of the total data available." {That is bull shit.} But the study didn't come as a surprise to some, including one The study could have a ripple effect, affecting prescribing guidelines and even prompting questions about how drugs

are approved. "This study raises serious issues that need to be addressed surrounding drug licensing and how drug trial data

is reported," one of the researchers said. In other words, all trial data needs to be made public. Also carried in BBC NEWS

at http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/7263494.stm |

|

|

||

|

From PLoS Medicine a peer review open access journal At http://medicine.plosjournals.org/perlserv/?request=get-document&doi=10.1371/journal.pmed.0050045 Initial Severity and Antidepressant Benefits: A Meta-Analysis of Data Submitted to the Food and Drug

Administration 1 Department of Psychology, University of Hull, Hull, United Kingdom, 2 University of Wyoming, Laramie, Wyoming, United States

of America, 3 Center for Health, Intervention, and Prevention, University of Connecticut, Storrs, Connecticut, United States of

America, 4 Department of Psychology, University of Windsor, Windsor, Ontario, Canada, 5 Institute for Safe Medication Practices, Huntingdon Valley, Pennsylvania, United States of America Background Meta-analyses of antidepressant medications have reported only modest benefits over placebo

treatment, and when unpublished trial data are included, the benefit falls below accepted criteria for clinical significance.

Yet, the efficacy of the antidepressants may also depend on the severity of initial depression scores. The purpose of this

analysis is to establish the relation of baseline severity and antidepressant efficacy using a relevant dataset of published

and unpublished clinical trials. Methods and Findings We obtained data on all clinical trials submitted to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

for the licensing of the four new-generation antidepressants for which full datasets were available. We then used meta-analytic

techniques to assess linear and quadratic effects of initial severity on improvement scores for drug and placebo groups and

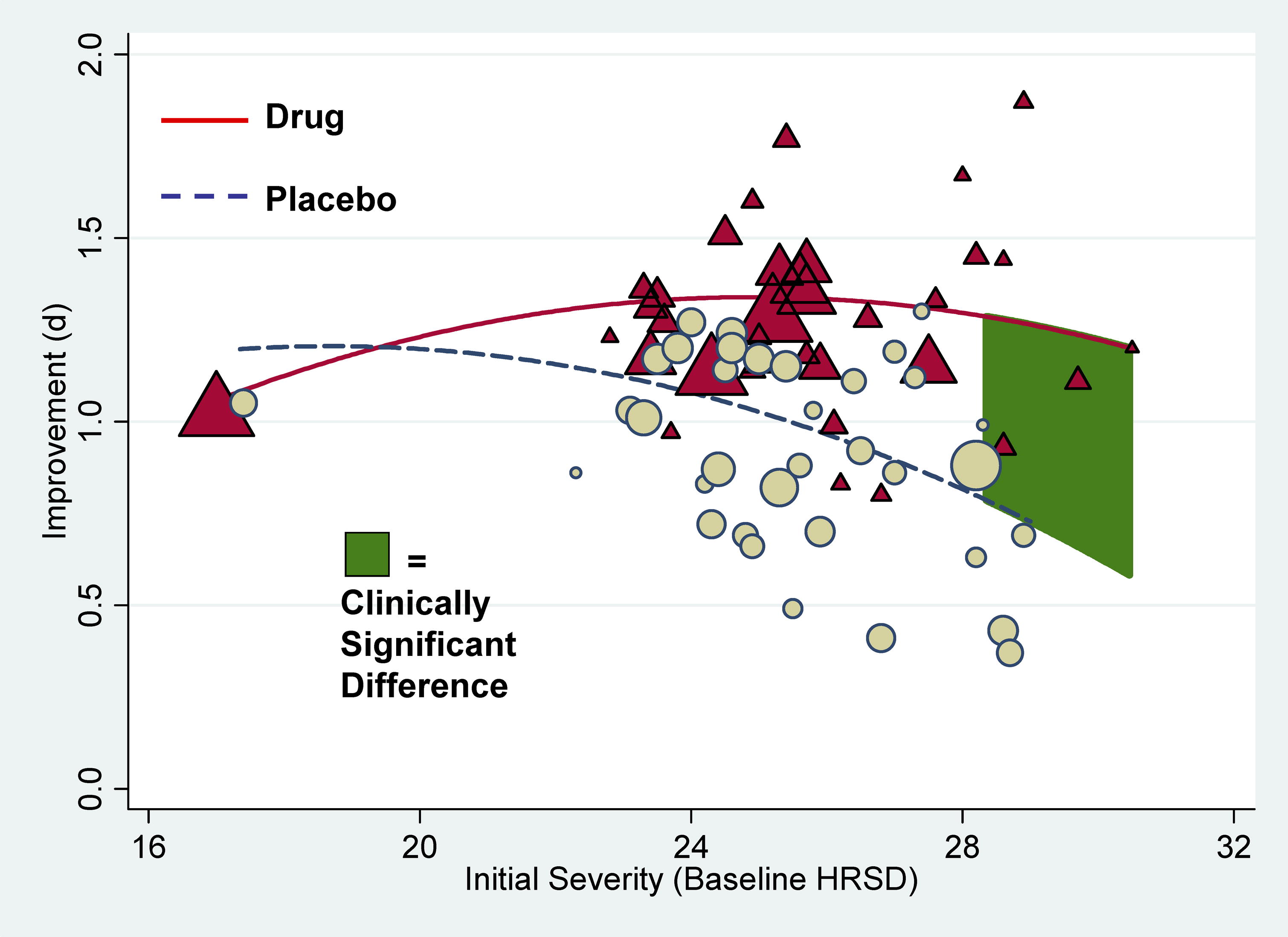

on drug–placebo difference scores. Drug–placebo differences increased as a function of initial severity, rising

from virtually no difference at moderate levels of initial depression to a relatively small difference for patients with very

severe depression, reaching conventional criteria for clinical significance only for patients at the upper end of the very

severely depressed category. Meta-regression analyses indicated that the relation of baseline severity and improvement was

curvilinear in drug groups and showed a strong, negative linear component in placebo groups. Conclusions Drug–placebo differences in antidepressant efficacy increase as a function of baseline

severity, but are relatively small even for severely depressed patients. The relationship between initial severity and antidepressant

efficacy is attributable to decreased responsiveness to placebo among very severely depressed patients, rather than to increased

responsiveness to medication. Funding: The authors received no specific funding for

this study.. Competing Interests: IK has received consulting fees from Squibb and Pfizer. BJD, TBH, AS, TJM, and BTJ have no

competing interests. Academic Editor: Phillipa Hay, University of Western

Sydney, Australia Citation: Kirsch I, Deacon BJ, Huedo-Medina

TB, Scoboria A, Moore TJ, et al. (2008) Initial Severity and Antidepressant Benefits: A Meta-Analysis of Data Submitted

to the Food and Drug Administration. PLoS Med 5(2): e45 doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050045 Received: January 23, 2007; Accepted: January 4, 2008; Published:

February 26, 2008 Copyright: © 2008 Kirsch et al. This is an open-access

article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution,

and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abbreviations: d, standardized mean difference; FDA, US Food and Drug Administration; HRSD, Hamilton Rating Scale of

Depression; LOCF, last observation carried forward; NICE, National Institute for Clinical Excellence; SDc, standard deviation of the change score *

To whom correspondence should be addressed. E-mail: i.kirsch@hull.ac.uk Background. Everyone feels miserable occasionally. But for some people—those with

depression—these sad feelings last for months or years and interfere with daily life. Depression is a serious medical

illness caused by imbalances in the brain chemicals that regulate mood. It affects one in six people at some time during their

life, making them feel hopeless, worthless, unmotivated, even suicidal. Doctors measure the severity of depression using the

“Hamilton Rating Scale of Depression” (HRSD), a 17–21 item questionnaire. The answers to each question are

given a score and a total score for the questionnaire of more than 18 indicates severe depression. Mild depression is often

treated with psychotherapy or talk therapy (for example, cognitive–behavioral therapy helps people to change negative

ways of thinking and behaving). For more severe depression, current treatment is usually a combination of psychotherapy and

an antidepressant drug, which is hypothesized to normalize the brain chemicals that affect mood. Antidepressants include “tricyclics,”

“monoamine oxidases,” and “selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors” (SSRIs). SSRIs are the newest

antidepressants and include fluoxetine, venlafaxine, nefazodone, and paroxetine. Why Was This Study

Done? Although the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the UK National Institute

for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), and other licensing authorities have approved SSRIs for the treatment of depression, some doubts remain about their clinical efficacy. Before an antidepressant is approved

for use in patients, it must undergo clinical trials that compare its ability to improve the HRSD scores of patients with

that of a placebo, a dummy tablet that contains no drug. Each individual trial provides some information about the new drug's

effectiveness but additional information can be gained by combining the results of all the trials in a “meta-analysis,”

a statistical method for combining the results of many studies. A previously published

meta-analysis of the published and unpublished trials on SSRIs submitted to the FDA during licensing has indicated that these

drugs have only a marginal clinical benefit. On average, the SSRIs improved the

HRSD score of patients by 1.8 points more than the placebo, whereas NICE has defined a significant clinical benefit for antidepressants

as a drug–placebo difference in the improvement of the HRSD score of 3 points. However, average improvement scores

may obscure beneficial effects between different groups of patient, so in the meta-analysis in this paper, the researchers

investigated whether the baseline severity of depression affects antidepressant efficacy. What Did the Researchers

Do and Find? The researchers obtained data on all the clinical trials submitted to the

FDA for the licensing of fluoxetine, venlafaxine, nefazodone, and paroxetine. They then used meta-analytic techniques to investigate

whether the initial severity of depression affected the HRSD improvement scores for the drug and placebo groups in these trials.

They confirmed first that the overall effect of these new generation of antidepressants

was below the recommended criteria for clinical significance. Then they showed that there was virtually no difference in the

improvement scores for drug and placebo in patients with moderate depression and only a small and clinically insignificant

difference among patients with very severe depression. The difference in improvement between the antidepressant and placebo

reached clinical significance, however, in patients with initial HRSD scores of more

than 28—that is, in the most severely depressed patients. Additional analyses indicated that the apparent clinical

effectiveness of the antidepressants among these most severely depressed patients reflected a decreased responsiveness to

placebo rather than an increased responsiveness to antidepressants. What Do These Findings

Mean? These findings suggest that, compared with placebo, the new-generation antidepressants

do not produce clinically significant improvements in depression in patients who initially have moderate or even very severe

depression, but show significant effects only in the most severely depressed patients.

The findings also show that the effect for these patients seems to be due to decreased responsiveness to placebo, rather than

increased responsiveness to medication. Given these results, the researchers conclude

that there is little reason to prescribe new-generation antidepressant medications to any but the most severely depressed

patients unless alternative treatments have been ineffective. In addition, the finding that extremely depressed patients

are less responsive to placebo than less severely depressed patients but have similar responses to antidepressants is a potentially

important insight into how patients with depression respond to antidepressants and placebos that should be investigated further. Additional Information. Please access these Web sites via the online version of this summary at

http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0050045. List of Antidepressant Drugs with Medication

Guides Anafranil (clomipramine) Pamelor (nortriptyline) Anti-depression medications which are touted as correcting

a putative neurological imbalance sell much better than the older generation of drug.

However. the understanding of the neurotransmiiter imbalances are too poorly understood, and as a consequence medications

aimed at them have proven generally ineffective. Moreover most without severe

depression have a behavioral problem for which there is not an underlying neurotransmitter foundation. Treating a behavior problem with a drug fails because the neural transmitter aren’t the cause. If drugs are to reduce the incidence of depression, they need to make him feel more

energetic. Stimulants do that, yet the drug taboo compounded by the fact that

most stimulants are off patent, has kept for over 40 years this approach from being widely used--jk. |

|||